Six months into the HomeSense project, Prof. Nigel Gilbert outlined the “interesting ethics issues” that required attention before the field trial could responsibly get underway in volunteer households.

In his presentation, “The Ethics of Sensors” at the 2016 ESRC Research Methods Festival in Bath, Nigel explained the ambition of HomeSense to enable social researchers to use digital sensors alongside self-reported methods and observations. The project is also assessing the extent to which householders might accept sensors in their homes for research, and the final output will be a set of guidelines for use in such studies.

More refined or automated applications of digital sensors in social research could, it’s hoped, lead to more effective assisted living and telecare services, or more efficient use of energy. But before experimenting with sensors in people’s households, some obvious, and less obvious, questions of ethics ought to be addressed.

Ethical issues that come to light

Nigel suggested five key issues, all of which require mitigation to avoid potential risks to participants or researchers, and to satisfy the University’s ethics committee:

* Informed consent

* Security

* Privacy

* Inferred meaning

* Data protection

Nigel discussed his thoughts on each and highlighted some of what he considered unresolved issues.

Informed consent

A standard requirement for studies on human subjects is obtaining informed consent but “it becomes difficult to understand what informed consent means in this context when participants also include other family members, especially children. Then there are the issues concerning consent from visitors during the study, and how that is delegated to the householders“, Nigel said.

Even more problematic is the issue of describing how the data will be used. “Since the project is all about finding what we can do with data and for a range of purposes, how, in such circumstances, can we explain it?”

Then there’s an issue as the study progresses, how a sufficient degree of informed consent can continue to apply, suggesting that reminders might be needed periodically about what has been consented to already in order to support their choices to either continue or withdraw from the study.

Security

It is essential that all data is encrypted at the point of collection in homes and to ensure that the meaning of encryption is clear to participants and they reassured that this requirement is met.

Another security issue concerns data retention, which might be unclear how to square. The Data Protection Act states (and now the GDPR), that data should be retained for the minimum time necessary, whereas RCUK policy suggests research data should be retained for 10 years.

Privacy

All household data would be anonymised, according to standards. However, there is still a risk of individuals within households identifying each other in anonymised data or discussions of the data. “So”, said Nigel. “there’s an issue we need to think about carefully there…”

“Also, as we’re collecting data 24/7 in people’s homes, there may be things going on that, perhaps, they wouldn’t be very keen on us knowing about, at all”.

“One obvious example of that is sex”, said Nigel. “An even more difficult category (of risk) is what if evidence is found of domestic abuse or violence? This is something where social research has answers, but we need to think in advance of what we would do if we found data that indicated somebody was abusing someone else in one of our households.”

“Should we report such things?”, questioned Nigel, adding… “How sure can we be?”

Data protection

According to the GDPR, data should not be exported outside the EU which excludes the use of certain data storage services, such as Google Drive or Dropbox.

To get the ‘go-ahead’, the field trial in households is subject to ethics review, requiring that it operates within standard legal and ethical frameworks. So, before the trial begins, answers are required to all these and more questions.

Ethical concerns on the ground

HomeSense has three main research strands: adapting and developing sensors for social research purposes; developing data collections methods and trialling them in homes; and creating tools for analysing the data that these sensors generate.

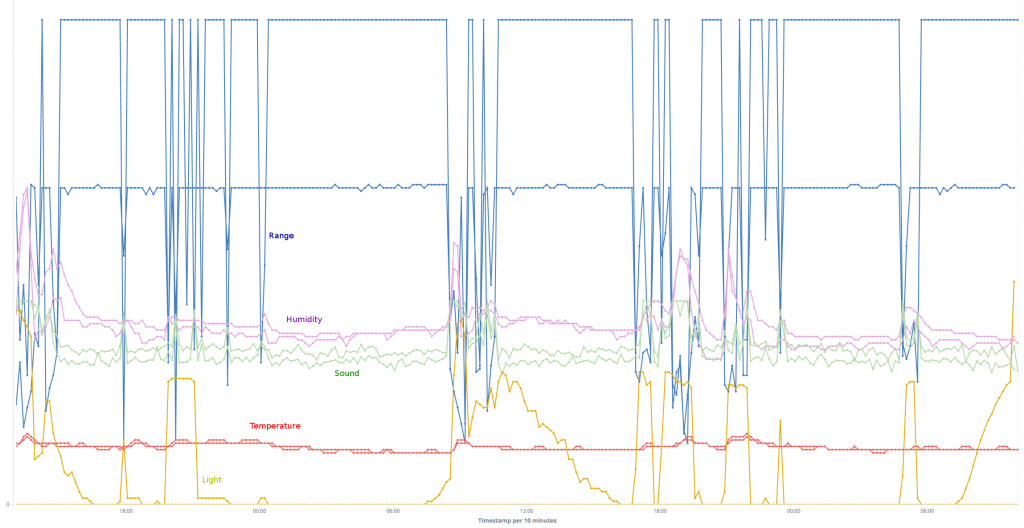

Fixed and wearable sensors have been installed in volunteer households already and the data is now being triangulated with time-use diary data, open-ended interview and questionnaire data, to form meaningful interpretations.

The fixed sensors detect noise levels, temperature, humidity, light, energy consumption and movement nearby, while the wearable sensors monitor participants’ location within their households.

According to lead researcher Kristrún Gunnarsdóttir, “There were two stages to obtaining ethics approval. Firstly, consulting all relevant academic material on performing research ethically and all relevant university guidelines on data management.”

“Secondly, the unique circumstances of this work with very intrusive methodological instruments, produce issues of how to explain the technology in an understandable way, and no one is going to want to read an essay.”

“So all the questions that arose presented us with quite a headache.”

A Participant Information Sheet was provided to all participants, designed to clearly describe the burden of participating, what would happen and what ethical and technical issues can arise. It outlines how consent, privacy and data security are taken care of.

However, ahead of actual installations in homes, the project team set up demonstrations of the sensor equipment to familiarise volunteer participants with the devices, what sort of data is collected and what it looks like to the researchers. Here they have an opportunity to see live data being generated, to see their effect on the data by playing around with the sensors, and have a conversation about what can be inferred from the data streams.

“This conversation became a turning point”, said Kristrún.

“I got the sense in my first visit to participants’ home that they were waiting for me to produce the technology from my bag”, and the degree of understanding we could achieve that way shows the power of demonstrating — or demystifying the technology.

“They wanted me to show them our toys”

“Often the fear is that being too transparent about what the technology is doing will cause people to run away, but actually it was quite the opposite. When it is explained they find it fun.”

“Discussion helps people and helps to build confidences. If you enter someone’s private environment it’s essential to risk a conversation and demonstrate.”

Risk assessment

By the new year of 2017, the HomeSense team had communicated with the ethics committee all relevant ethics issues, and conducted a risk assessment, concluding that the level of risk to participants and researchers was ‘low’ in all cases, provided that all aspects of the fieldwork would be carried out according to the plan elaborated in the ethics review application.

All things considered, the project’s ethics application to the University of Surrey Ethics Committee weighed in at 54 pages in length, including a tabulated risk assessment across six pages.

A number of special considerations turn on the use of sensors as opposed to other observational methods.

For example, the category of ‘right to choice and self-determination’ declared that participants would be free to make choices about where to install sensors and to omit any part of the household if they deemed it necessary. Consent would only be confirmed after household members participated in the hands-on demonstration, along with a conversation about the sort of information the data imply, and to what extent the method is acceptable to them. Children living in households would be involved at this stage with the opportunity to assent or object.

On the matter of confidentiality, researchers would reassure participants about data anonymity by explaining how sensor-generated data and potentially sensitive information is handled, while also ensuring that participants would have a choice at any time to turn off any one, more or all fixed and wearable sensors.

To safeguard the ‘internal confidentiality’ of households, the assessment states that efforts will be made to learn from preliminary observations, to anticipate activities and interactions involving any member of a household that may not be known or appreciated by another member. Further, to respect internal confidences, the researchers would not share sensor-generated data streams with participants that involve the presence and activities of other household members.

The more technical aspects of managing data streams, encryption, transmission, storage and structuring, were organised so that an illegitimate interception of the data for capture/theft, would yield only ‘garble’. In other words, an outsider accessing the sensor-generated data would not only have to decrypt the data but would also need to have on hand all the details on how the data is coded, structured and formatted, the configuration of the database environment and more, in order to make any sense of it. An intruder would not be able to associate data with a particular household or distinguish noise vs humidity data, so on and so forth. Those ‘other’ details would only be accessible via the work computer of the lead computational researcher on the team and only actionable by someone with considerable expertise in software programming, database and systems engineering.