With the HomeSense field trial completed, now is an opportunity to share some of the lessons learned on the way to capturing good data.

The technical aspects of this methodological trial were crucial to sort out. The learning process (by doing) highlighted some of the limitations of sensor-based technology in capturing socially relevant information, but other methodological issues in designing the trial, including ethical considerations, were equally important to get right.

Building and adapting devices

As seen in this illustrative HomeSense field trial timeline, the initial task (from April 2016) was to adapt and develop the ICS Desk EGG — to build firmware and software and test the reliability of its built-in sensors for measuring variable levels of airborne particulates, sound, vibration, temperature, humidity, light and objects/bodies moving in and out of range.

Other sensors of interest were electricity monitors and wearable activity monitors like Fitbit or similar. Most of May 2016 was devoted to testing wristbands (Apple Watch, ActiWatch, Fitbit and MiBand), and comparing the measurements taken from two or more of those simultaneously on the arms of researchers (and helpful colleagues) over days at a time. We chose MiBand for the trial, given a combination of favourable qualities such as the accuracy of measure (compared to other types), long-lasting battery (~3 weeks), easy access to the sensor-generated data, and a simple, waterproof design.

Deciding on electricity monitors was rather more long-winded. Myriad of proprietary monitors and user controls may be ideal for individual householders who can access data visualisations on their smartphones or dedicated monitors — but, the only type of kit with which we could tap directly into the sensor-generated data had been used by our colleagues working on the WholeSEM project. This adaptation of the monitoring kit was aimed at merging data from different points of electricity use with the environmental data captured by the EGG(s) in the same location, say, in a kitchen, living room or study.

A controlled ‘lab’ environment vs a real-life house

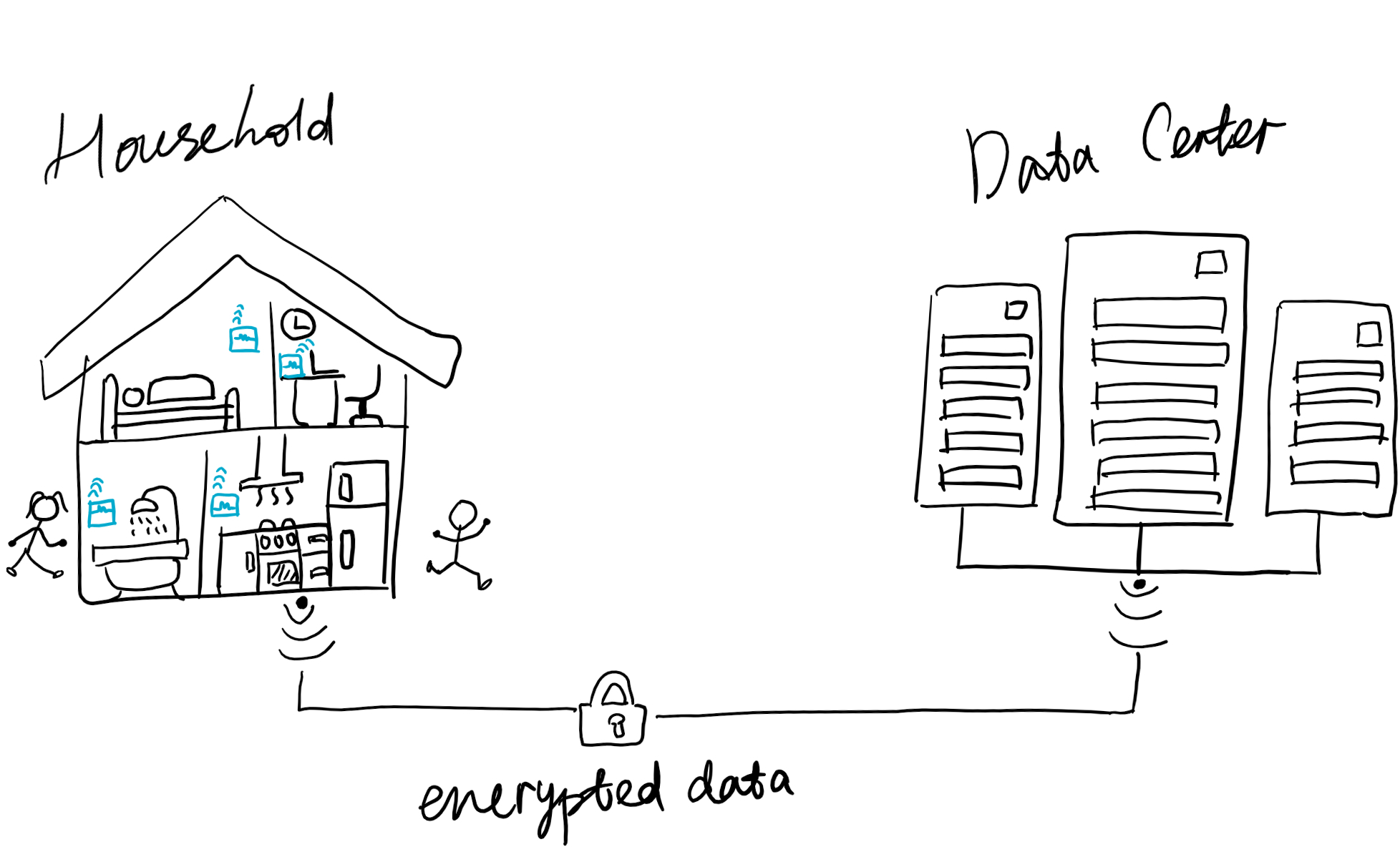

In a controlled environment we could configure and test everything — how to get the most out of the built-in sensors of the EGG, how best to utilise the wristband data, and the energy monitoring data. We set up a data-server, database environment and encrypted data transmission over networks.

We also wrote a participant information package, designed a guide for walking interviews, a questionnaire and time-use diary and consent forms. The next step was to test all these research instruments to uncover the many ways in which they would inevitably go wrong when taken into a ‘living’ household of a generous friend.

Just making sense of the situation in an actual household can be quite a barrier. An immediate problem is finding adequate locations to fit the sensors and discovering how critical that is. We were dealing with all sorts of fixtures, arrangements of furniture, and great variability in how rooms are used and which objects are on the move, so to speak.

Then we realised that some (older) router models wouldn’t work, and we were unsure about the reliability of automated posting of data through household routers over to our data centre. Reliability issues topped the list of concerns, such as how to manage network downtime without losing data and how much monitoring of the data streams would be required on our end for enquiries if one or more sensors were detected as offline. We were also testing the adaptation of the energy monitoring kit, hence, not entirely sure how reliable it would be.

These issues called for more development work but the living environment was also a test of other research instruments. For example, it was important to find out how effective the interview guide was for eliciting sufficient information about household activities during a walking interview and, similarly, whether the questionnaire was adequately ‘tuned’ for the purpose of understanding the household. The environment seemed rather chaotic, making it hard to make sense of what was going on in the data, in particular, as we realised that we would not see any direct evidence of social interaction. The wristband sensor was giving us the overall activity data of the wearer both at home and away, but perhaps if it gave us instead just the location of the wearer within the home, we could improve upon our contextualisation of household activity data.

The information package appeared to make sense and the consent form covered all the relevant points, but we weren’t well prepared for children, shared households, erratic lifestyles, dogs, hamsters, and the many contingencies of ordinary, everyday home life…

In parallel with this test, the ethics review application was being drafted. Getting friends and acquaintances on board was helping us to see what we were getting ourselves (and prospective participants) into, and which steps to take in order to carry out the field trial in a responsible and acceptable manner. The resulting application was submitted in September 2016.

Second Test House

While we waited for the review from the ethics committee, we started a second test installation. Further development had been done to improve the EGGs, make installation and the monitoring of data streams easier to oversee, and we were getting better at finding places to fit the EGGs.

Running through to November and December, this second test of the research instruments in a two-person household looked out for anomalies and unforeseen issues and demonstrated the use of all the relevant paperwork.

Ethics approval and all systems go…

A favourable review from the ethics committee of a revised application came in February 2017, the key issues turning on ensuring adequately informed consent from all types of participants, including those who participate indirectly.

We had revised the field trial design to include a demonstration of sensors and data-streams in action to complement our information package, followed by discussion with prospective participants — to explain the technology and the purpose of the study and ensure good understanding.

Related content: Demystifying the technology important for ensuring the confidences of field trial participants

Recruiting for the field trial

The first publicity medium of choice was flyers, posted around the Guildford campus, as well as in town, in community centres, and online bulletin boards, but the response wasn’t all that encouraging as just two people got in touch with us. Then, in the month of May 2017 we got on board with the Festival of Wonder, celebrating the 50th anniversary of the University of Surrey.

This event attracted thousands of people from across southern England, interested in ‘show-and-tell’ science. The HomeSense team hosted an exhibition area (a simulated home), titled ‘Making sense of the 21st century household’, in which the field trial technology was demonstrated.

The demonstration was successful at engaging this public audience and it pushed the recruitment process forward. Our guests played around with the sensor suite, observed and discussed with the researchers what/how the sensors can capture, and a number of them expressed interest in taking part in the trial.

The response was made up of households more geographically dispersed than we’d envisioned, from Chertsey to Portsmouth, but only about a third of those who initially got in touch and received an information package, followed through to actual participation.

Recruitment wasn’t exactly easy, in part because the HomeSense field trial isn’t problem-specific, apart from being a methodological trial of using sensors to study social life. If we’d recruited for something problem-specific, for example a medical condition, we’d have been working with a Health Trust and GPs targeting people with a particular condition and applying sensors to monitor, say, a recovery or a medication regime. Recruiting would have had a very different outlook.

Next, we posted flyers around Guildford (in community centres, churches, and other such places) which resulted in participation of a few more households, sufficient for us to think, ‘Okay. Well, this is going to be all right’.

The field trial (June to Dec 2017)

Installations were carried out from June up until beginning of October with active data collection in each household lasting for 10-13 weeks.

All equipment was collected before the Christmas vacation and it was clear already that we had good data from thirteen households, but we wanted at least 20.

Extending the trial

To attract more households, flyers were distributed directly through the letterboxes of homes in Guildford and surrounding villages in the beginning of December — in time to generate interest ahead of the vacation and schedule first appointments right after the New Year.

By mid-January 2018 we’d installed in a few more households and in March 2018 (finally) the field trial was complete.

Household trial an example to be covered in our courses

The field trial considers a very particular setting (the household) for applying sensors in social research. However, during the project we learned about all sorts of sensors and issues to do with using them for research purposes.

Tips, tricks and examples from the field trial will be shared in our courses in partnership with National Centre for Research Methods (NCRM). The first such course Using Sensors in Social Research is accepting sign-ups for 10 and 11 September 2018.

The course will cover many types of sensors and situations in which they can be applied, data types, collection methods, visualisation and analytic methods, and a range of ethical considerations in using this technology.

We’ll keep you up-to-date with our latest news as these courses are scheduled. You can also keep up to date via our presence on Twitter or LinkedIn.

Related content: Short course Using Sensors in Social Research for research practitioners requiring latest knowledge in the use of digital sensors.